1. Główna idea: „Współ-inteligencja”

Ethan Mollick w swojej książce Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI proponuje nie patrzeć na AI (sztuczną inteligencję) jako na rywala, ale jako na partnera w myśleniu i działaniu — stąd pojęcie co-intelligence (współinteligencja).

Kilka kluczowych punktów:

- Współczesne systemy generatywnej AI, zwłaszcza modele językowe („large language models” – LLM), działają w sposób niezwykły: przetwarzają ogromne zbiory tekstów, uczą się wzorców językowych i pomagają nam generować nowe teksty, pomysły, analizy.

- AI to jak „obcy mózg” („alien mind”) – coś, co nie myśli jak człowiek, ale może z nami współpracować. Tę metaforę Mollick wykorzystuje, by podkreślić: musimy nauczyć się żyć i działać z tym „obcym”

- W efekcie chodzi o stworzenie nowego stylu pracy i uczenia: człowiek + maszyna, każdy wnosi to, co najlepiej potrafi. AI przejmuje pewne zadania, człowiek trzyma stery, nadzoruje, decyduje.

Uczeń-kucharz: jak AI naprawdę się uczy

- Mollick używa genialnej metafory: uczeń-kucharz.

Wyobraź sobie młodego kucharza, który chce zostać mistrzem.

Ma spiżarnię pełną składników (czyli weights – wagi, których w ChatGPT jest 175 miliardów), ale kompletnie nie wie, jak ich używać. - Przed nim miliony przepisów (teksty z Internetu, książki, artykuły). Uczeń zaczyna próbować.

Miesza, łączy, myli się, poprawia. Z czasem odkrywa, że jabłka pasują do cynamonu, a kmin do kawy już nie.

Z każdą próbą jego spiżarnia staje się bardziej uporządkowana, aż pewnego dnia zaczyna gotować dania, które naprawdę mają smak.

- To właśnie etap pre-trainingu — uczenia bez nadzoru człowieka (unsupervised learning).

AI obserwuje wzorce, zależności, rytm języka, aż zaczyna pisać spójnie i naturalnie.

Ale uwaga: to wciąż uczeń bez zrozumienia. Umie powtórzyć przepisy, ale nie wie, dlaczego smakują dobrze.

Pre-training i jego cienie

- W tej fazie AI pochłania ogromne ilości tekstów — publiczne, naukowe, czasem również te objęte prawem autorskim.

Nie kopiuje ich, lecz przekształca w matematyczne wzorce — tzw. wagi, które mówią jej, jak prawdopodobne jest, że słowa wystąpią razem.

To tworzy nową, trudną granicę między nauką a prawem, inspiracją a własnością. - Mollick pisze, że dobre dane mogą się skończyć już za kilka lat. Firmy będą musiały nauczyć AI uczyć się z mniejszej ilości treści — albo tworzyć dane samodzielnie.

- I tu pojawia się paradoks: AI uczy się z ludzkiej kultury, ale nie tworzy jej znaczeń. Jest jak papuga, która zbudowała bibliotekę cytatów, ale nigdy nie przeżyła ani jednej emocji z tych książek.

Fine-tuning — lekcje z ludzkiego feedbacku

- Kiedy AI już „ugotuje” danie, człowiek musi je spróbować.

To etap fine-tuningu — czyli uczenia z pomocą ludzi.

Eksperci czytają odpowiedzi AI, oceniają je („👍” lub „👎”), a model uczy się, jakie formy i tony są pożądane.

To proces zwany RLHF — Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback.

- W ten sposób AI zaczyna nabierać smaku – rozumieć, że nie każda odpowiedź dobra statystycznie jest dobra społecznie.

Że można mówić poprawnie, ale nieodpowiedzialnie.

Że nie wszystko, co się da wygenerować, powinno zostać wypowiedziane.

2. Cztery zasady współ-inteligencji

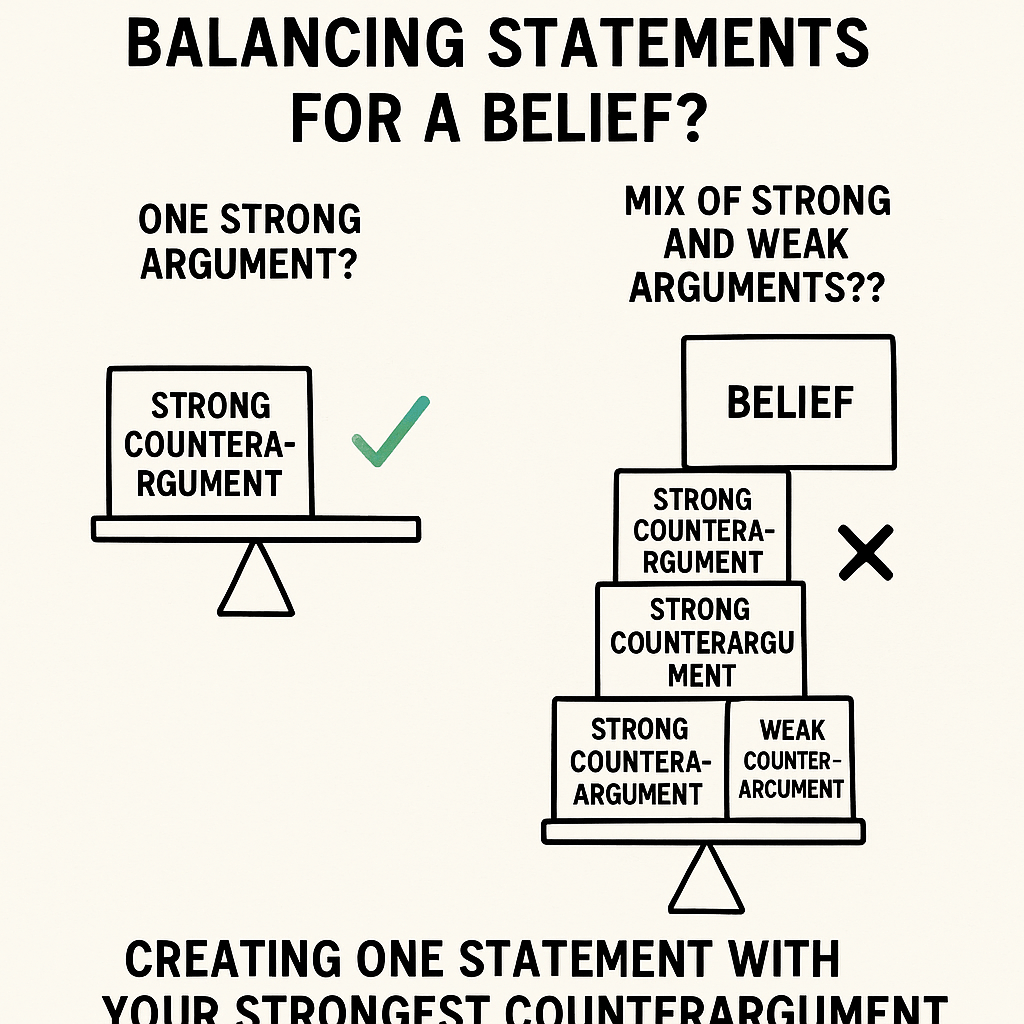

Mollick przedstawia cztery podstawowe reguły, które pomagają efektywnie współpracować z AI.

- Zawsze zaproś AI do stołu („Always invite AI to the table”). Eksperymentuj, sprawdzaj: „czy w tym zadaniu AI może pomóc?” — bo jeśli nie spróbujesz, nie poznasz granic (tzw. „jagged frontier”).

- Bądź człowiekiem w pętli („Be the human in the loop”). Oznacza to: nie odchodź od nadzoru — AI może sugerować, ale decyzje i odpowiedzialność są po stronie człowieka.

- Traktuj AI jak osobę (ale jasno zakomunikuj, jaką osobą) („Treat AI like a person — but tell it what kind of person it is”). Czyli: ustaw kontekst, persona, rolę dla AI; dzięki temu efekty mogą być lepsze.

- Zakładaj, że to najgorsze AI jakie kiedykolwiek użyjesz („Assume this is the worst AI you’ll ever use”). Technologia rozwija się błyskawicznie — to, co dziś jest najnowsze, jutro może być przestarzałe.

Te zasady warto pamiętać szczególnie w edukacji, w pracy, w uczeniu się — bo pomagają uniknąć fałszywego przekonania, że AI zastąpi człowieka lub że wystarczy „klikać i patrzeć”.

3. Uczenie się, edukacja i rola AI

- Mollick podkreśla, że podstawowe umiejętności i wiedza faktograficzna wciąż są kluczowe — zanim zaczniemy korzystać z AI, powinniśmy mieć solidne fundamenty. Bez nich trudno zauważyć wzorce, wyłapać błędy, zrozumieć kontekst.

- W edukacji AI może pełnić role: tutora (indywidualna pomoc, dostosowanie się do ucznia) i trenera/coacha (wsparcie w rozwoju umiejętności, analiza, feedback) — Mollick omawia te role jako część części drugiej książki.

- Przykład: architekt-student, który co tydzień spotyka się z ekspertem vs. drugi student, który po każdym projekcie otrzymuje natychmiastowy feedback od AI — ten drugi może robić więcej iteracji, szybciej uczyć się.

- W edukacji tradycyjny model (nauczyciel przekazuje, uczeń odbiera) musi ewoluować. AI może przejąć część pracy — np. dostarczanie materiału, powtórki — a nauczyciel może skupić się na tym, co najludzkie: wyjaśnianie, prowokowanie pytań, mentoring.

Gdzie AI może mieć ograniczenia w edukacji

- AI mogą halucynować: generować odpowiedzi, które brzmią przekonująco, ale są nieprawdziwe — więc uczniowie muszą nauczyć się weryfikować, krytycznie myśleć.

- AI nie zastąpi całkowicie ludzkiego nauczyciela: feedback, emocje, relacje, motywowanie — te elementy pozostają silnie ludzkie. Mollick sugeruje, że nauczyciel-mentor jeszcze bardziej zyskuje na znaczeniu.

- Uczenie „jak pisać zapytania (prompt-engineering)” to nie wystarczy. Książka zauważa, że kluczowe jest nie tylko umiejętność „składania promptu”, ale rozwijanie krytycznego myślenia, świadomości zadania i kontekstu.

4. Różne role AI

Mollick wyróżnia kilka „persona” AI: jaką może pełnić rolę w naszym życiu zawodowym, edukacyjnym, twórczym.

- AI jako osoba („AI as a person”) — czyli kiedy przypisujemy mu cechy, rolę eksperta, wspólnika. Użyteczne, jeśli wiemy, jak ją skonfigurować.

- AI jako kreatywna siła („AI as a creative”) — generowanie pomysłów, twórcze kombinacje, wsparcie w procesie tworzenia. Jednocześnie: nie wszystko, co wygeneruje, będzie wartościowe.

- AI jako współpracownik („AI as a coworker”) — w pracy: automatyzacja pewnych zadań, wsparcie analityczne, szybkie wersje robocze, ale człowiek dalej ma przewagę w wyborze, kierowaniu, ocenianiu.

- AI jako tutor („AI as a tutor”) — w edukacji: zadania dostosowane, feedback, wsparcie indywidualne; ale z zastrzeżeniem kontrolowania jakości i nie oddawania całej interakcji maszynie.

- AI jako coach („AI as a coach”) — w rozwoju umiejętności, w karierze: co mogłoby pójść źle? co mogę zrobić lepiej? – AI może stawiać pytania, proponować scenariusze, zmuszać do refleksji.

5. Wagi: co wynika dla uczenia się, edukacji, rozwoju?

- Uczenie się w erze AI oznacza przejście od pamiętania do rozumienia i tworzenia — skoro AI może pomagać w generowaniu faktów, to my musimy skupić się na umiejętnościach wyższego rzędu: krytycznym myśleniu, dyskusji, kreatywności.

- Edukacja powinna uwzględniać integrację AI w procesie, nie tylko je blokować. Uczniowie powinni uczyć się „jak współpracować z AI”, a nie tylko „jak go unikać”.

- Nauczyciele i trenerzy powinni stać się bardziej projektantami procesów uczenia się, mniej tylko przekazującymi wiedzę, a bardziej umożliwiającymi współdziałanie człowieka i maszyny.

- W rozwoju zawodowym: osoby, które nauczą się wykorzystywać AI jako współpracownika, będą miały przewagę — ale nadal kluczowe pozostaje, by człowiek pozostał w roli decyzjodawcy, kreatora, nadzorcy.

- Trzeba być świadomym ograniczeń AI — czyli że AI może wprowadzać błędy, może być „za dobre”, popaść w pułapkę automatyzacji bez refleksji — odbierając nam to, co najcenniejsze: ludzką perspektywę.

6. Gdzie AI „nie jest dobre” – czyli ograniczenia AI

- AI często halucynuje — generuje błędne lub zmanipulowane informacje, bo nie „rozumie” świata, tylko przewiduje słowa.

- AI może być nadmiernie pewne siebie — brzmi „mądrze”, ale nie zawsze jest to prawda. Wymaga więc weryfikacji przez człowieka.

- AI nie ma świadomości, wartości, intencji — choć może symulować osobowość, to jednak nie jest człowiekiem. Trzeba uważać, by nie nadawać mu cech, których nie ma.

- AI nie zastąpi w pełni ludzkich relacji, motywacji, intuicji — w edukacji oznacza to: nie redukujemy nauczyciela do maszyny; nie likwidujemy rozmowy, zrozumienia, wspólnego procesu.

- AI może zmniejszyć różnicę między ekspertami a laikami — co z jednej strony jest szansą, ale z drugiej stawia pytania o wartość i odrębność wysokich kompetencji.

7. Podsumowanie

W erze generatywnej AI największą przewagą człowieka będzie to, co człowiecze – ciekawość, krytyczne myślenie, etyka, tworzenie znaczenia. A AI jest partnerem, który może nam pomóc szybciej dojść dalej — pod warunkiem, że my nadal prowadzimy, decydujemy i nadzorujemy.

Uczmy się nie tylko zapytania (jak „promptować”), ale jak myśleć, jak oceniać, jak współdziałać z AI – bo to współ-inteligencja będzie dominującą formą uczenia się i pracy.